Part 3: The financial state of the outpatient dialysis clinic

Ever wondered how much money a dialysis clinic actually makes?

It was my Mom’s birthday yesterday, so I wanted to start by saying Happy Birthday Mom! Thank you for everything!

***

As outlined in Part 2, the ESRD patient experience is heavily centered around outpatient (OP) dialysis providers, and I believe understanding their business is critical to deeply understanding ESRD. For that reason, I want to analyze a single OP clinic and answer the following questions:

OP Dialysis Clinic Financial Performance: What does the annual income statement for a single clinic look like?

Payer Mix: How sensitive is the financial success of the business to the payer mix?

DaVita was deemed the benchmark/proxy for this analysis as it is a public company (thus has publicly available information) and is heavily focused on delivering dialysis in the United States. All analyses are linked at the end.

Outpatient Dialysis Clinic Financial Performance

Revenue

To start, ~91% of DaVita’s total $11.6B in revenue comes from U.S. dialysis patient service revenue, and 76% of U.S. dialysis patient service revenue is generated via OP clinics. These metrics illustrate how dialysis providers often have limited diversification across both services and modality. Fresenius is an outlier given its medical device business, but nearly 70% of its revenues still come from dialysis.

Nevertheless, we can estimate OP dialysis revenues (based on DaVita’s reported revenue mix) and divide it by the number of OP clinics to find that average revenue per OP clinic per year is ~$2.9M (Row G).

Chart 1: Total revenue per OP clinic

Costs

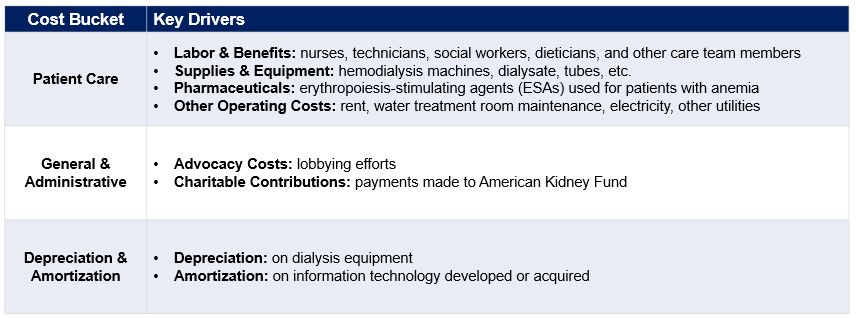

OP clinic costs are primarily concentrated in patient care, but also include general and administrative (G&A) expenses as well as depreciation & amortization (D&A). A quick summary of key cost drivers:

Chart 2: Key OP clinic cost drivers

DaVita reports these three cost buckets in sum, not split by OP, home, and inpatient dialysis. It is not fair to assume cost allocation is the same as the revenue mix (76%/18%/6% as in Chart 1), so to get OP-specific costs, I made the following assumptions:

Patient care costs: Allocated more towards OP since it is more labor-intensive than home and inpatient dialysis (85%).

G&A costs: Allocated at the same rate as revenue (76%).

D&A: Split between OP and home dialysis under the assumption hospitals own dialysis machines and technology and thus dialysis providers avoid most D&A when providing inpatient services (81%).

Based on those assumptions, the average total cost per OP clinic per year is ~$2.6M+ (Row N).

Chart 3: Total costs per OP clinic

Gross & operating margins

Combining Charts 1 & 3, my projections indicate an OP clinic has a 25% gross profit margin and 10% operating profit margin.

Chart 4: Income statement for single OP clinic

To reiterate, this analysis uses DaVita clinics as a proxy for all clinics, and their financial position will differ from that of smaller clinics. I believe the following represent the most unique differences:

Revenue (Quantity): Smaller clinics lack the affiliated nephrologist network and clinic footprint necessary to capture the same volume of patients.

Revenue (Pricing): Smaller clinics have less bargaining power and are more likely to agree to lower reimbursement rates when negotiating with private insurers (driving down gross profit).

G&A Costs: Smaller clinics likely spend less on lobbying and/or charitable contributions to AKF and thus G&A spend is lower.

Commentary on recent market activity

In 2022, both Fresenius and DaVita invested outside their core business of OP dialysis. Fresenius created a NewCo with Interwell and Cricket Health focused on integrated, value-based kidney care while DaVita created a NewCo with Medtronic focused on developing innovative, kidney care-focused medical devices. Both Fresenius and Davita have also openly discussed how home dialysis is a strategic priority (and even formed a home dialysis partnership!).

What’s driving this shift? My initial hypothesis was that OP revenue and its already-low margins were declining, prompting providers to invest in higher margin growth opportunities. However, as Chart 5 indicates, that hypothesis is incorrect as OP clinic financial performance has remained largely unchanged since 2019.

Chart 5: OP clinic financial performance (2019-21)

In addition to the ongoing scrutiny faced by dialysis providers, I believe the strategic shift is due to a combination of the following:

Shrinking Patient Pool[1]: Between 2019 and 2021, DaVita’s total US patients served dropped from 206,900 to 203,100, likely driven by COVID-19 (i.e., 15K ESRD patients estimated to have died[2]) and ongoing improvements in earlier-stage CKD treatment.

Margin Sensitivity: OP clinics have limited wiggle room as gross and operating margins are only 25% and 10%, respectively. Cost-wise, multiple forces such as mandated staffing ratios (like Proposition 29 in California) and increasing healthcare labor costs could further suppress margins.

Defensive Move: By investing in new areas, DaVita and Fresenius have increased the remaining market share needed for new, disruptive competitors to breakeven, disincentivizing new competition from entering the arena.

Payer Mix:

Part 2 cited the large discrepancy in reimbursement in 2022 between private insurers (i.e., employer, individual), and government programs (i.e., Medicare Advantage, Original Medicare), but how does that dynamic impact OP clinic profitability and strategy?

Revenue per treatment by payer was not reported separately, so using DaVita’s terminology, I calculated it as follows:

Gov’t Programs: Includes Original Medicare, Medicare Advantage, Medicaid, Managed Medicaid. Average revenue per treatment is estimated at $282 (Row B). This is the average of the Original Medicare and Medicare Advantage rates for 2021 – $253 and $311, respectively (slightly less than 2022).

Commercial: Includes employer-sponsored and individual health plans. Average revenue per treatment is estimated at $1,161 (Row B). This is the average of the employer and individual rate provided in Part 2 – $1,476 and $846, respectively.

We can then estimate revenue and gross profit by payer at both the patient and clinic-level.

Chart 6: Patient-level revenue and gross profit by payer type

Chart 6 highlights how Gov’t Programs are almost certainly run at negative operating margin since gross margin is 4% (Row F). Also, Commercial patients are worth more than 90x Gov’t Program patients in terms of gross profit (Row G)!

Chart 7: Clinic-level revenue and gross profit by payer type

Chart 7 shows that not unlike other healthcare services, the cash flow from Gov’t Programs is needed (Row M/N, $2M+ in revenue!), but Commercial patients are what fuel profitability (Row P). That dynamic is exacerbated in this space and explains why dialysis providers must acquire and protect commercially insured patients (i.e., individual and employer) at all costs. To date, at least DaVita has done this successfully as its Commercial patient mix has remained at 10% the last three years[3].

This overreliance on a single service and segment creates business model risk as dialysis providers are highly susceptible to any competition or regulation (e.g., AB 290 from Part 2) capable of capturing or reducing the value of commercially insured patients.

Implications of Marietta Memorial Hospital Employee Health Benefit Plan vs. DaVita

As referenced briefly in Part 2, Marietta Memorial created an employee health plan where all dialysis providers were deemed out-of-network and thus not covered by the plan, potentially exposing their employees with ESRD to substantial out-of-pocket costs. In June, SCOTUS ruled in favor of Marietta Memorial, thereby allowing them to keep dialysis providers out-of-network and potentially setting a precedent for other employers to follow suit.

If other employers adopted this network structure, ESRD patients would have three options:

Option 1: Stay on the employer plan and pay out-of-pocket for dialysis (i.e., $1,000+ per treatment)

Option: 2 Move to Medicare and subsidize the 20% coinsurance per treatment (discussed in Part 2) with secondary insurance

Option 3: Enroll in an individual health plan (likely subsidized by AKF) presumably during open enrollment; pay limited out-of-pocket

Options 2 and 3 are clearly most economical for patients, but how the transition off Option 1 works in practice is unclear. Regarding Option 2, would newly diagnosed ESRD patients have to pay out-of-network bills for the first three months before Medicare coverage starts? Regarding Option 3, would patients have to wait until open enrollment to leave their employer plan for an individual plan?

Regardless, since dialysis providers need patients to choose Option 3 to stay in business, expect even more charitable contributions to AKF. However, it is worth noting that the scope of the SCOTUS decision’s impact remains to be seen. It is unclear how many employers will put dialysis providers out-of-network (like Marietta Memorial Hospital did) and how many ESRD patients even get insurance from their employers (less than 20% of patients on dialysis are still employed)[4].

We will see how it plays out, but either way, SCOTUS’ decision exemplifies the regulatory risk dialysis providers face because of their business model.

Parting shot

To me, the data paints the OP dialysis clinic as a business model that lacks diversified revenue streams, has tight margins and is susceptible to competition as well as adverse policy changes. History tells us these businesses will need to change at some point (and they are slowing starting!), so I am excited and hopeful for a future focused more on improving the patient experience and/or diversifying into new services and payment models.

***

Links to: Sources | Graphics (PPT) | Analysis (Excel)

If you have any reactions or want to talk kidney care, digital health, etc., you can reach me on Twitter @z_miller4 or connect with me on LinkedIn here!

Great work! - given the Type 1/2 patients you mentioned in part 2, seems like going upstream to value based CKD management also enables improved management of the patient funnel for DaVita/Fresenius, as well as potential to improve their overall health before they potentially fall into a value based ESRD bundle - could help reduce total cost of care.