For the true The Post-Op experience, read Part 1 first as Part 2 will resonate more if you do! Nevertheless, let the imperfect and chaotic graphic below sink in before we unpack it further.

Chart 1: Attempted depiction of the ESRD value chain

Payers[1]

Original Medicare (Part A & B) & Medicare Advantage

Medicare covers anyone with ESRD regardless of age. Coverage for dialysis starts on the first day of the fourth month of dialysis or as early as the first month under certain conditions. This three-month waiting period starts before signing up for Medicare, and patients’ private insurer may provide coverage during that time. Coverage for kidney transplants begins the month patients are admitted to a hospital for a kidney transplant or other transplant-related services.

Medicare Part A covers inpatient dialysis treatments while Part B covers outpatient treatments, home-based treatments, certain drugs, and other support services[2]. Once the Part B deductible is met, patients pay 20% coinsurance for covered dialysis-related services ($257.90 per treatment in 2022), historically with no out-of-pocket cap. Oftentimes, a secondary payer (i.e., supplemental Medicare, Medicaid, or commercial plan) will cover these out-of-pocket costs. Without the secondary payer, Part B patients would pay $8,000+ out-of-pocket for dialysis annually (i.e., $233 deductible + [$257.90 per treatment * 20% coinsurance * 3 treatments per week * 52 weeks per year])!

Medicare Advantage (MA) is becoming increasingly prevalent for ESRD patients as the 21st Century Cures Act allowed any Medicare-eligible beneficiary to enroll in MA. Prior to Cures, patients could only enroll in MA if they had enrolled prior to ESRD diagnosis[3].

Private Insurance

Federal law allows patients to keep private insurance (i.e., employer-sponsored or individual plans) for 33 months before enrolling in Medicare. The 3-month waiting period and 30-month requirement incentivize insurers to keep patients from progressing to ESRD. Without it, insurers would theoretically want the patient to reach ESRD since they could then offload expenses to Medicare[4].

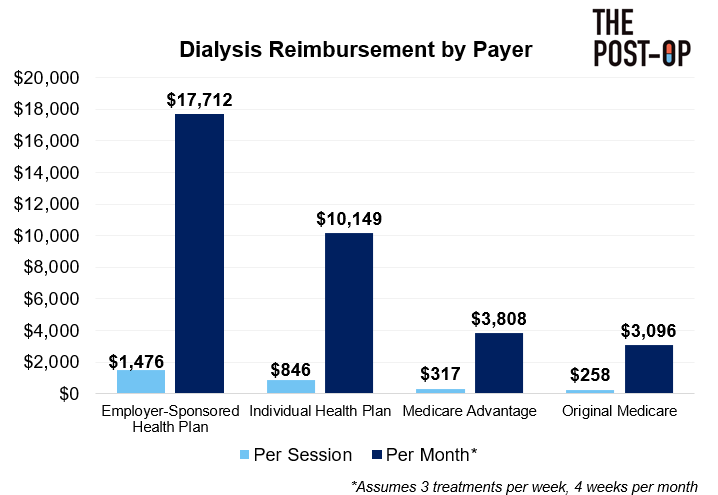

In 2019, 37% of ESRD patients had private insurance (Employer & Individual), 25% Medicare Advantage, 23% Original Medicare, 9% Dual Medicare/Medicaid, and 6% Medicare Secondary Payer[5]. The payer mix is important to note as dialysis providers receive substantially higher reimbursement for patients with private insurance.

Chart 2: Dialysis reimbursement by payer[6],[7],[8]

If you are interested in the June 2022 SCOTUS ruling in Marietta Memorial Hospital Employee Health Benefit Plan vs. DaVita and its implications on insurance options for ESRD patients, we’ll cover that in Part 3!

American Kidney Fund

You cannot talk about ESRD and insurance without discussing the American Kidney Fund (AKF), a non-profit focused on fighting kidney disease. The AKF has a Health Insurance Premium Program (HIPP), helping ESRD patients (71K in 2021) fund individual insurance premiums via grants[9].

In 2021, AKF made $350M in Total Support and Revenue with $347M coming from contributions[10]. It has been reported that nearly 80% of the AKF budget ($280M+!) is funded by DaVita and Fresenius, the two largest dialysis providers[11]. Their contributions to AKF are used to pay individual health insurance premiums for HIPP patients, costing ~$500 per patient per month[12]. As Chart 2 indicates, individual health insurance pays significantly more than Medicare, so dialysis providers are heavily incentivized to keep patients on individual insurance for as long as possible.

The ‘Difference’ column below shows how dialysis providers’ arrangement with AKF accelerates profit generation as for every $500 donated (Row B), providers make an additional $6,000+ per month (Row C). This practice places a greater cost burden on individual plans and in turn raises premiums across the entire market. Unsurprisingly, the arrangement has drawn scrutiny from legislators and in 2019, California bill AB 290, which limited reimbursement to dialysis providers for privately insured patients in programs like HIPP, was signed into law. AB 290 has since been halted, but similar bills continue to emerge.

Chart 3: Incremental profit per patient from AKF arrangement

Dialysis Providers

Dialysis can be performed in inpatient, outpatient (i.e., in-clinic), or home-based settings. The space is dominated by outpatient, and market power resides in two companies, DaVita and Fresenius. There are 7,000+ clinics in the US, and ~90% are for-profit organizations.

Chart 4: Dialysis facility market share breakdown[13]

Factors to understand about outpatient dialysis providers:

Staffing: Key staff include dialysis nurses (overseeing the clinic), patient care technicians (performing/monitoring treatment), and biomedical technicians (maintaining dialysis machines and water quality). Clinics must also employ a social worker and renal dietician, both of which must meet with each patient at least monthly.

Nephrologist relationships: More on this below, but each clinic must be under supervision of a certified nephrologist or “medical director”. In addition, other nephrologists “affiliate” with certain clinics, meaning they have an agreement to “round” (or regularly check-in) with their patients at these clinics. Nephrologists can affiliate with multiple clinics.

Patient acquisition: Patients either have a relationship with a nephrologist who diagnoses them with ESRD (Type 1) or lack a nephrologist and are suddenly diagnosed with ESRD after going to the hospital for another emergency (Type 2). Nephrologists refer patients to clinics where the nephrologist is affiliated (especially Type 1 since a relationship exists) and/or clinics close to the patient’s home. Type 2 patients are often referred to multiple clinics near their home, and the first clinic to “accept” gets the patient. Anecdotally, I have heard the split is 35% Type 1, 65% Type 2.

Inorganic growth: DaVita and Fresenius have leveraged M&A to fuel growth. For example, DaVita acquired eight US-based clinics in 2020 and seven in 2019[14].

Kidney Transplant Enablers[15]

Part 1 mentioned how ~90,000 are on the kidney transplant waitlist but only ~24,000 transplants were performed. Making this worse is the fact that the average life expectancy for dialysis patients is roughly 5 years, but that number increases to 8-12 years for deceased donor transplants and 12-20 years for living donor transplants[16]. Refer to the bottom right of Chart 1 and then we’ll dive into how it works.

The Organ Procurement & Transplant Network (OPTN) is a non-profit created via federal statute to run organ procurement and distribution nationwide (not just kidneys, but livers and hearts as well). OPTN is comprised of Organ Procurement Organizations (OPOs), transplant centers, labs testing for organ compatibility, and other services.

The United Network of Organ Sharing (UNOS) is a private, non-profit organization that has been under contract with the government for the past 36 years to run OPTN. The contract is estimated to be worth ~$6M annually, and UNOS pocketed an additional ~$47M in 2021 from fees paid by patients to be listed for transplants[17].

UNOS’ responsibilities include maintaining the transplant waitlist, determining policies for prioritizing patients on the list, reviewing mistakes made by OPTN members, and running the technology connecting OPTN. UNOS, and its technology in particular, have recently been under scrutiny as investigations indicate they are unable to track organs from Point A to B, rely heavily on manual data entry, and run on local data centers. UNOS is technically overseen by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), but HRSA can only “monitor” that UNOS is following contractual obligations rather than pushing them to innovate.

Within OPTN, CMS has designated 57 Organ Procurement Organizations (OPOs) that manage organ procurement, recovery, and allocation to transplant centers within a designated geography (called donation service areas). OPOs also provide clinical management of organ donors and education about organ donations.

Last, there are 250+ kidney transplant centers[18] in the US (essentially hospitals credentialed to perform transplants). Candidates are referred by their nephrologists and must undergo medical and psychosocial approval, a fairly rigorous process managed by the center, to be accepted onto the transplantation list[19]. Once accepted, patients are registered in the national, computerized list, maintained by UNOS.

Nephrologists[20]

Core nephrologist responsibilities include seeing patients with renal/kidney issues (pre-ESRD), diagnosing them with ESRD (as necessary), making referrals for dialysis or kidney transplants, and checking-in with patients throughout treatment. Nephrologists may also perform interventions/procedures to create access for dialysis (e.g., artery-vein (AV) fistula surgery) and may support patients throughout the transplant process (e.g., determining patient-donor compatibility).

Relationship with dialysis clinics

As mentioned, nephrologists refer ESRD patients to dialysis clinics. Nephrologists are affiliated and “round” at select clinics, so if a patient wants to see their nephrologist during dialysis, they must receive treatment at a clinic where their nephrologist is affiliated.

Additionally, nephrologists may have a financial stake in the clinics where they are affiliated as many dialysis clinics are operated as joint ventures (JVs) between dialysis providers and nephrologists[21]. For example, DaVita reported JVs generated 28% of its $10.6B+ in US dialysis revenues (so ~$3B overall)[22].

Stark Law prohibits physicians from referring Medicare or Medicaid patients to clinics where they have a financial relationship. Without getting into the weeds, Stark Law excludes services paid under a “composite rate”, and organizations like DaVita believe that the ESRD PPS bundled payment (discussed more below) constitutes a composite rate and thus is excluded from Stark Law[23]. Unbound by Stark Law, nephrologists in these JVs technically have financial incentives to prescribe dialysis too early or to steer patients to their co-owned clinics rather than recommending a kidney transplant. I do not know how these incentives impact nephrologist behavior in practice.

Select Federal Agencies

Compared to other conditions, the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) have shown a greater willingness to invest in and experiment with programs hoping to reduce costs and enhance quality in ESRD.

CMS controls the ESRD Prospective Payment System (PPS)[24], setting the rate Medicare pays dialysis facilities. As mentioned, this year’s rate was $257.90[25], and it is ‘bundled’ into a single payment covering the cost of drugs, labs, supplies, maintenance, etc. for each dialysis session.

CMS’ ESRD Quality Incentive Program (QIP)[26] is a downside-only program incentivizing delivery of high-quality services at dialysis facilities by reducing the PPS rate by up to 2% based on performance against certain measures.

CMMI has experimented with innovative payment models such as the Comprehensive ESRD Care (CEC) Model[27], ESRD Treatment Choices (ETC) Model[28], and Kidney Care Choices (KCC) Model[29] (comprised of the Kidney Care First (KCF) Option and Comprehensive Kidney Care Contracting (KCC) Option).

Chart 5: Summary of CMMI’s ESRD value-based programs[30],[31],[32]

Others Important Stakeholders

Caregivers: Oftentimes a family member responsible for hygiene, provision of medications, transportation to dialysis center, and emotional/mental support[33].

Digital CKD Platforms: Payers sometimes attribute portions of their population to companies like Cricket Health, Strive Health, and Somatus who manage the care of CKD/ESRD patients with the goal of limiting CKD progression and/or ESRD complexities. These digital-first platforms employ nurses, social workers, and dieticians that, together, and are focused on educating patients and helping patients execute the care plan provided by their nephrologist (e.g., going to appointments, taking medications, etc.).

Parting shot

To close, I want to zoom out, simplify, and share my main takeaways:

Dialysis providers have built business models around the delivery of in-clinic dialysis to privately insured patients worth 3-5x more than Original Medicare patients.

To acquire patients, dialysis providers must have a strong network of affiliated nephrologists and/or clinics near patients’ homes.

The dialysis and kidney transplantation markets are a true duopoly and monopoly, respectively, which may limit incentives to innovate.

We’ll discuss these areas deeper throughout the series, and I hope you stick around for it.

***

Links to: Sources (footnotes are also linked) | Charts (PPT) | Analysis (Excel)

If you’d like to discuss ESRD or anything healthcare-related, you can ping me on Twitter @z_miller4 or connect with me on LinkedIn here!

This is such a great summary, thanks @thepostop and @Tim F. for sharing

Interesting stuff! Can you explain why MA plans pay more than Medicare FFS for Dialysis? I thought that MA plans usually just paid the FFS rates for provider services. I was able to find this, but it doesn't answer the question of why the facilities are able to negotiate higher rates and stay in-network...

"In an interesting twist, providers can charge more in the Medicare Advantage market by being in network. If a patient goes to an out-of-network provider, the provider is prohibited from charging more than traditional Medicare,” said Erin Duffy, research scientist at the USC Schaeffer Center. “But when there are only one or two providers in a market, the insurance company loses any potential leverage to negotiate lower payments.”