Part 2: How public schools operate at the intersection of healthcare and education

A step-by-step breakdown of the government-funded process

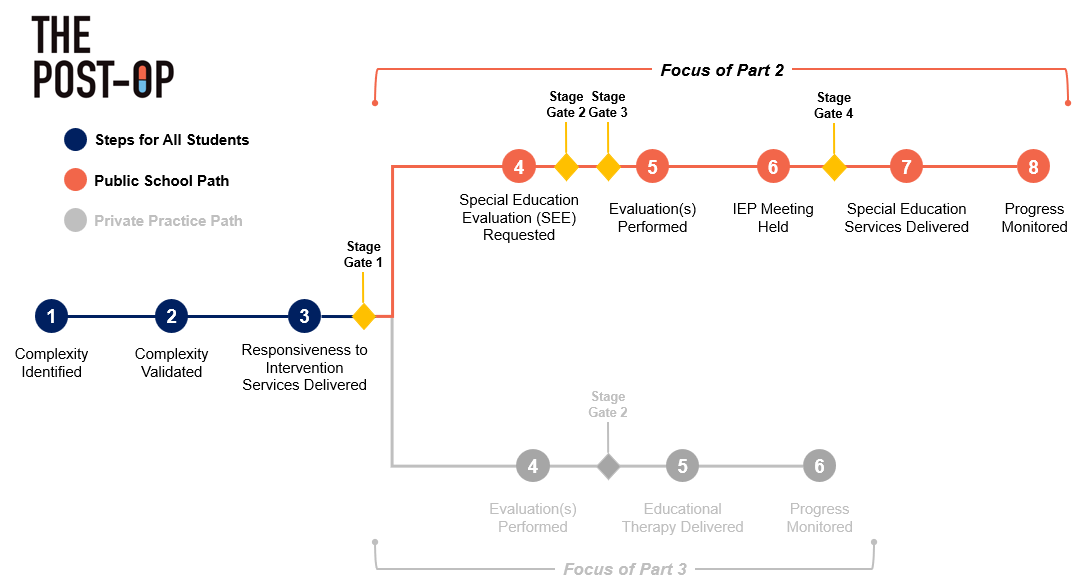

Part 1 described LDs generally, but the reality is there are two distinct paths for those struggling with LDs. In Parts 2 and 3, we’ll unpack both paths by looking closely at the steps, stage-gates, and stakeholders involved.

Chart 1: The divergent paths of learning differences

Steps for All Students

Steps 1 & 2: Complexity Identified & Validated

Parent(s) or teacher notice the student is exhibiting LD-related symptoms (e.g., working slowly, struggling with memorization, writing illegibly) and subsequently confirm the other party is also noticing symptoms. Together, they may begin gathering work samples, notes, etc. in case a more thorough evaluation becomes necessary.

Step 3: ‘Responsiveness to Intervention’ (RTI) Services Delivered[1]

RTI services aim to distinguish between inadequate instruction and an actual LD as the source of learning failures and to avoid either unnecessary Special Education Evaluations (SEE) or unnecessary referrals to neuropsychologists. RTI services are required (by federal law) to be delivered in public schools but are also commonly delivered in private schools. In both cases, RTI services provide data needed to build students’ case for special education services.

Students receive different RTI services based on need and progress. Ideally (though not always), this would include 1) general education with some adjustment to address specific students’ needs (e.g., assignments with less math problems), 2) small group instruction, or 3) more intensive, oftentimes 1:1 instruction[2],[3]. In general, RTI services are a form of “early intervention” discussed in Part 1.

Stage-Gate 1 – Were the RTI services effective?: The teacher assesses the student’s progress by looking at performance on examinations (relative to the class average and/or benchmarks of expected performance at that time of the year) and work samples to determine whether an SEE should be requested (Public School Path) or a referral to a neuropsychologist for further evaluation should be made (Private Practice Path).

The paths diverge after Stage-Gate 1, so hereafter, we’ll focus solely on the Public School Path.

Public School Path

Step 4: SEE Requested

The Individuals with Disabilities Act (IDEA) requires schools conduct evaluations of students that may have a disability or are failing in general education. This evaluation seeks to determine the student’s special education needs and may be requested if RTI services were deemed ineffective (Stage-Gate 1). The request includes information from Step 3 like the student’s performance relative to benchmarks, work samples, and teacher observations.

Stage-Gate 2 – Is the SEE necessary?: Schools must perform the SEE if, based on the information provided, there is reason to believe a disability exists. Common reasons for SEE rejection include the student just started school and is still “developing”, student is still performing at grade-level or above, student’s struggles stem from behavioral rather than LD issues (e.g., ADHD) or student’s performance is improving due to the RTI services[4].

Stage-Gate 3 – What should be evaluated during the SEE?: If an SEE is necessary, a psychologist (employed by the school/district) will work with the parents and teachers (among others) to determine the SEE’s scope. Together, if being diligent, they review the student’s educational history, observe classroom behavior, and analyze data gathered to-date. Ultimately, the goal of this is to determine the skills to be tested (via academic achievement tests) and what, if any, non-LD, specialty tests are needed (e.g., tests for hearing or speech issues).

Despite oftentimes causing the student’s issues, cognitive abilities (tested via IQ tests discussed in Part 1) are not typically assessed because the school is only legally obligated to address academic-related challenges.

Chart 2: Public school evaluation

Step 5: Evaluation(s) Performed

The psychologist administers the academic achievement tests while, as needed, other specialist (often employed by the district) such as ophthalmologists, audiologists, or speech-language pathologists also perform their evaluations. Results are gathered before the Individual Education Program (IEP) meeting is held.

Step 6: IEP Meeting Held[5],[6],[7]

IEP teams include parents, school psychologist, general education teacher, special education teacher, a district representative, and a case manager (sometimes the special education teacher) responsible for coordinating IEP execution[8]. This group applies the diagnostic principles detailed in Part 1 and reviews academic achievement test results to identify areas (e.g., reading, writing, math, etc.) where the student is substantially underperforming benchmarks (i.e., at/below 30-40th percentile for their grade). Some districts emphasize educational history and classroom observations as much as test scores whereas others determine need based on test scores alone.

Stage-Gate 4 – What special education services are needed?: If the IEP team concludes the student meets the district’s criteria and has an LD, the student officially becomes eligible for an IEP. The IDEA governs IEP creation and requires IEPs include:

Student’s present levels of educational performance (academic and/or functional)

Measurable annual goals as well as how progress will be measured and reported

Special education services and accommodations required as well as start date, frequency, location, and duration

Understood.org provides a good example of what these elements look like on paper:

Chart 3: Example IEP[9]

Variability in IEP decisions due to state benchmarks

As mentioned, no uniform approach to special education service determination exists, but academic achievement tests performance is a common throughline. Test performance is oftentimes assessed by comparing results to local or national averages, and this approach can cause students to go undiagnosed and thus untreated.

Chart 4 illustrates how, even within regions, state averages can vary materially and thus become susceptible to this dynamic.

Chart 4: Average 4th grade math & reading score range by region[10]

For example, say Kyle from West Virginia’s average reading and math score is 220 – 4.5 points higher than West Virginia’s average (215.5), but 5.5 and 13 points lower than the averages in US and Florida (a fellow Southeastern state), respectively. Despite performing below the averages nationally and in another Southeastern state, Kyle may be deemed ineligible for an IEP because he outperformed the average in his state.

Step 7: Special Education Services (or Accommodations) Delivered

Nevertheless, once the IEP is finalized, the school becomes obligated to provide the student special education services, accommodations, or both.

Special Education Services: Location, intimacy, and frequency are key variables. For example, while the general education class learns math, the student(s) with dyscalculia may be “pulled-out” of the classroom to work with the special education teacher on math or said teacher will be “pushed-in” to deliver instruction in the general education classroom. Instruction may be delivered in 1-on-1 or small group settings as frequently as multiple hours daily or infrequently as only a couple hours (sometimes even minutes!) monthly. Part 1 outlines the ways in which instruction is delivered. See “Services” section of Chart 3 for an example.

Accommodations (aka 504 Plans)[11]: Students in 504 Plans do not receive instruction from special education teachers. Instead, they remain in the general education classroom, but receive accommodations to support their needs. Accommodations range from getting preferential seating or extended time on testing to using a calculator or speech-to-text technology during exams. 504 Plans are governed by Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, a federal civil law aiming to stop people discrimination against people with disabilities.

Variability in access due to state funding[12]

States receive “categorical grants” from the federal government to be spent on special education and have discretion on how to allocate these grants to school districts. For example, 30 states (including Washington, D.C.) provide districts a minimum-guaranteed dollar amount per special education student.

Chart 5 highlights how these amounts vary nationally and regionally.

Chart 5: Special education per-student funding range by region[13]

Districts use these funds to employ special education teachers and purchase instructional materials, and if funds are insufficient, districts cover the shortfall with general purpose funding. Thus, the funding districts receive for special education directly impacts their ability to employ special education teachers, and inadequate supply of teachers has consequences. It can lead to unnecessary rejections of IEP requests and may impact instruction effectiveness as students receive instruction in small groups settings (rather than 1-on-1) or less frequently than needed.

As Chart 5 illustrates, there are large state-to-state differences in funding per-student, meaning an LD student’s access to treatment can be highly dependent on their home state.

Step 8: Progress Monitored

Referenced in Stage Gate 4, IEPs must contain details on goals and progress reporting, all of which is determined by the IEP team using the datapoints we’ve been discussing. “Annual goals” section of Chart 3 provides an example of both goals and progress reporting.

In that example, the special education instructor must measure Karen’s words read per minute in late second-grade passages as well as the accuracy with which she reads both unfamiliar 2- and 3-syllable words and 180 high-frequency words. The instructor must also provide parents quarterly progress reports on said metrics. Theoretically, the instructor should be adjusting their approach throughout the quarter based on Karen’s progress, but the reality is instruction happens privately, making it difficult for parents to monitor adjustments to instruction.

Parting shot

Robert Frost wrote “Two roads diverged in a wood, and I – / I took the one less traveled by / And that has made all the difference”.

The Public School Path is unfortunately the road more traveled by for LD treatment, meaning we rely on the notoriously bureaucratic and under-funded public education system to treat an issue that has serious implications on children’s long-term health and well-being.

I believe we can do better. That starts with thinking of LDs as a healthcare issue more than an education issue, and the rest of Season 2 will explore this idea from different angles.

**

Links to: Sources | Graphics (PPT) | Analysis (Excel)

If you want to chat further about LDs or anything healthcare-related, follow me on Twitter @z_miller4 or connect with me on LinkedIn!

If you are an early-stage startup and potentially interested in my support for any unit economics or financial modeling-related activities, please fill out the form here.